2ND AMENDMENT EXPLAINED

The 2nd Amendment does not, and never has, guaranteed a constitutional right for individual Americans to own guns.

First, a little history…

Under the first constitution that governed the nation’s founding, the States had an express right to maintain and arm their militia. The 2nd Amendment was drafted out of fears that the proposed U.S. Constitution—shifting to Congress the power “to provide for organizing, arming, and disciplining Militia”—left the States’ right to arm their militias merely implied, and subject to federal tyranny.

In ratification debates, Federalists like James Madison who drafted the amendment, assured: “I cannot conceive that this Constitution, by giving the general government the power of arming the militia, takes it away from state governments.” John Marshall, later chief justice, said: “If Congress neglects our militia, we can arm them.” But Antifederalists like Patrick Henry rejected assurances that “states have the right of arming” militia, warning “implication will not save you, when a strong army” comes. “If gentlemen are serious when they suppose a concurrent power, where can be the impolicy to amend it?”

The Antifederalists won this war powers dispute, and an amendment that preserved the States’ right. Its wording, and how it gave States what they demanded, have long mystified scholars and the courts. Unable to explain either, gun control and rights advocates asked the Supreme Court in District of Columbia v. Heller (2008) to choose between two rights never debated—of individuals to serve in the militia or to self-defense—that the majority and dissents each called absurd. No one argued, and the Court never addressed, the right actually debated and protected. Read more

Let’s walk through how the amendment’s precise use of language begins to reveal its plain meaning.

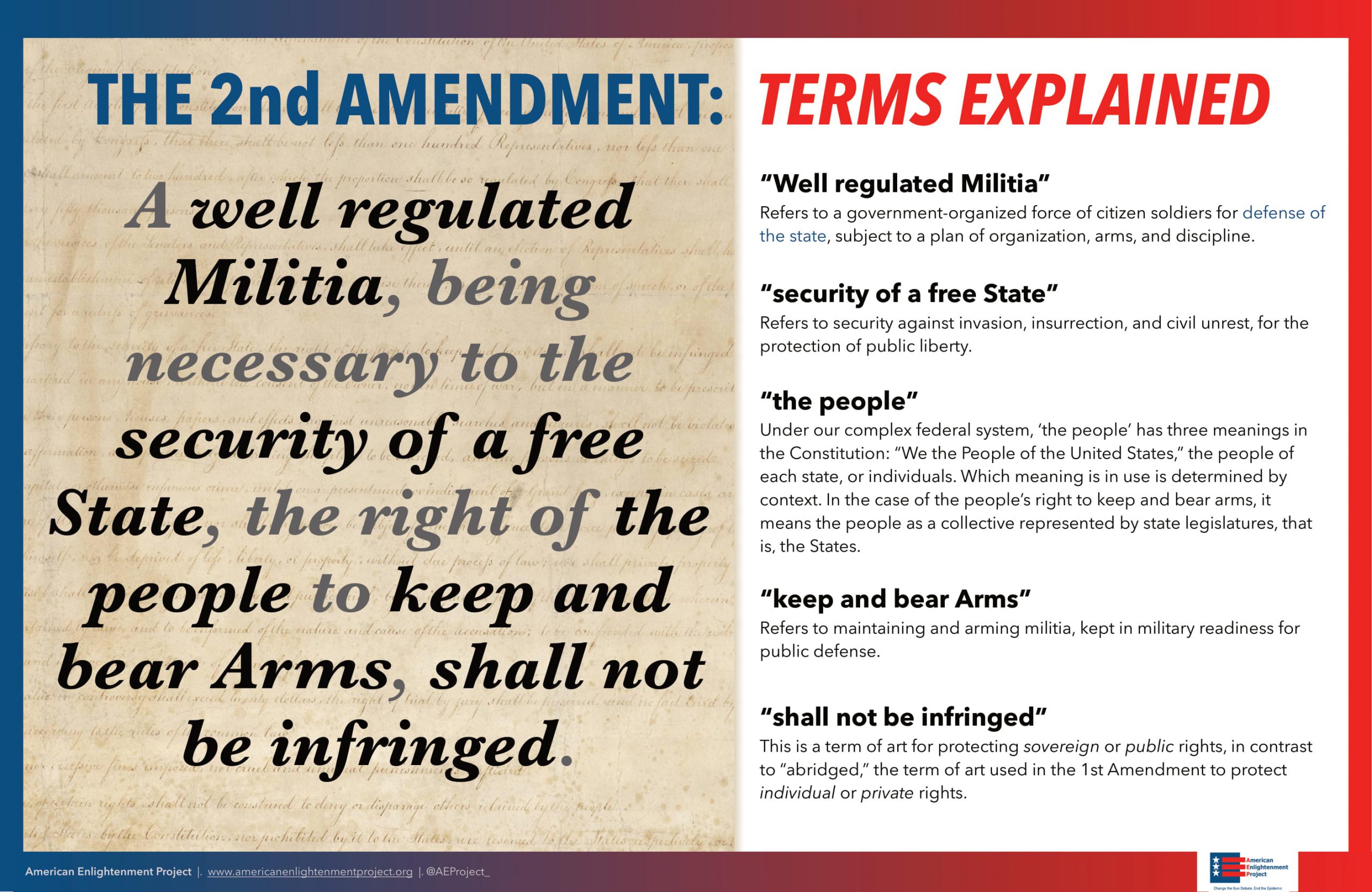

The Terms Explained

These meanings have not been self-evident, though they should be.

Guesswork over Two Thirds of the Amendment

Constitutional scholars have long considered the 2nd Amendment “baffling” and its first two clauses hopelessly contradictory. Throughout the 20th century, most courts focused on its prefatory clause— “A well-regulated Militia, being necessary to the security of a free State”—to conclude its purpose was to protect state militias.

In 2008, however, the Supreme Court in Heller dismissed that preface and focused on the rights clause — “the right of the people to keep and bear Arms” — to find, for the first time, an implied right to own a gun for self-defense, a “right” not found in the text or debated at founding. Citing dictionaries and little founding support — essentially guessing — Heller rewrote the amendment into an unconstitutional artifice.

Among its many glaring errors, Heller changed:

- well regulated to “disciplined”—turning the governing first constitution (from “well-regulated and disciplined militia” to “disciplined and disciplined militia”), and with it the amendment, into nonsense

- militia to “citizens’ militia”—conflating “citizen soldiers” and “militia” into an oxymoron

- the people to individuals rather than the States—ignoring context, including the unique prefatory clause it reduced to nonsense, and unusual last clause it ignored

- keep and bear to “possess and carry”—missing an idiomatic use of keep, and dismissing that of bear

- arms to personal weapons—uncritically perpetuating a fiction

- infringed to “abridged”—carelessly transposing terms of art, not even synonyms

Remarkably, scholars, courts, and both sides of the gun debate ignored the last clause—“shall not be infringed”—on which the amendment rests, that helps illuminate its meaning. Heller twice carelessly transposed infringed to abridged, never deciding the actual constitutional text.

Infringe vs. Abridge

In constitutional usage, these two terms refer to different types of right, public vs. private. Though sometimes loosely used interchangeably, as the Court in Heller and McDonald did, they are not synonyms as is obvious from any thesaurus.

Abridge refers to individual rights – for example the 1st Amendment uses abridged when prohibiting Congress from curtailing a private right to freedom of speech.

Infringe refers to encroachment on a public or sovereign right – in other words, a right held collectively by the people as a sovereign body, like a State.

For over 200 hundred years, this nation has overlooked why infringe and abridge are used in its Constitution. Without knowing how such terms were used in the 18th century, one cannot begin to understand the story.

-

Abridged then and today

In 1789, after Madison used abridge in drafting the 1st Amendment to protect the “great rights” of freedoms of speech, assembly, and petition, the Senate rejected the House’s substitution of infringe, correcting what the founders called a “solecism,” or the ungrammatical use of terms.

This corrected usage has continued to this day. Every single amendment since the Bill of Rights that protects individual rights uses the term abridge, never infringe:

- 14th (1868): “No State shall make or enforce any law which shall abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States….”

- 15th (1870): “The right of citizens … to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude.”

- 19th (1920): “The right of citizens … to vote shall not be denied or abridged … on account of sex.”

- 24th (1964): “The right of citizens … to vote … shall not be denied or abridged … by reason of failure to pay any poll tax or other tax.”

- 25th (1971): “The right of citizens … to vote shall not be denied or abridged … on account of age.”

- Equal Rights Amendment (prop. 1972): ‘‘Equality of rights under the law shall not be denied or abridged … on account of sex.”

-

Infringed then and today

Infringed is used in the 2nd Amendment to protect a State’s right to maintain a militia.

In 1789, the Senate rejected the House’s ungrammatical substitution of infringe in the 1st Amendment, reinstituting Madison’s use of abridge for individual rights.

In drafting the 2nd Amendment, Madison, the House and Senate all used infringed, to protect State sovereignty. (Tellingly also, Madison drafted the 2nd Amendment as a limit on Congress alone, unlike the 1st Amendment which he proposed as a limit on both Congress and the States.)

This distinction was familiar during the decades of American protests against the British Parliament’s “taxation without representation,” expressed as infringements of the sovereignty of colonial legislatures, and distinguished from individual rights not to be abridged.

In the past 230 years since the ratification of the 2nd Amendment, infringe has never once been used in any of the amendments protecting individual rights, which always use the term abridge.

To this day, infringe is used to protect public, not personal rights. Garner’s Dictionary of Modern Legal Usage (1995), defines infringe as “infringe on [read encroach or impinge on] British sovereignty.” Garner was a frequent co-author of the late Justice Scalia who wrote Heller, using dictionaries to define every term of the amendment, except infringed.

Correcting a related misconception post-Heller, a 7-2 Supreme Court reaffirmed it “has long recognized” patent infringement involves a “public right,” overruling the dissent that “most everyone considered an issued patent a personal right.” That 2018 decision in Oil States Energy v. Greene’s Energy by Justice Thomas, a staunch defender of Heller, did not ask why patent infringement is never called patent abridgement. The answer: a patent protects a territorial right granted for a limited period by a sovereign government.

So, what does this mean? Quite simply, it means the 2nd Amendment has nothing to do with an individual’s right to own a gun. It unambiguously refers to a public, not private, right. Just as the 1st Congress corrected the ungrammatical substitution of infringe for abridge, we should care enough about our Constitution and language to try to understand, not contort or misuse them.

The 2nd Amendment and the Militia System

If the 2nd Amendment doesn’t protect an individual’s right to own guns, what right does it protect? To answer this, we must reexamine the amendment not only in light of the plain meaning of all its terms — briefly explained above, including the verb on which it rests — but also the militia system on which it is based.

In 1939, a unanimous Supreme Court placed the militia system at the core of the amendment, explaining in United States v. Miller: “In all the colonies, as in England, the militia system was based on the principle of the assize of arms.” The assize was an 1181 English law which revived an ancient right of the sovereign to maintain militia. The amendment exists to preserve that right for States.

Through the ages, the militia system’s enduring features were:

- government organization of citizen soldiers for defense of the state

- specified arms kept in readiness

- a compulsory duty to serve, enforced by specified discipline

Variable elements of the institution were:

- who supplied arms, the state or militiamen (as an indirect tax)

- where to keep them, in public stores or the home

These elements were often used in combination. For example, the first constitution, the Articles of Confederation, required States to “keep up a well-regulated” militia and “a proper quantity of arms” in “public stores”—duties that some, under crushing war debt, shifted to militiamen.

This historic model was reenacted in centuries of Anglo-American militia acts. Citing this history, Miller held: “With obvious purpose to assure the continuation and render possible the effectiveness of such forces, the declaration and guarantee of the Second Amendment were made. It must be interpreted and applied with that end in view.”

Throughout the 20th century, federal appeals courts across the country, following Miller, held the amendment was meant, as one summarized, “solely to protect the right of the states to keep and maintain armed militia.”

-

Read More

- Thomas v. Portland (1st Cir. 1984) (by panel including later Justice Breyer: “grants right to the state”)

- United States v. Toner (2d Cir. 1984) (“right to possess a gun is clearly not a fundamental right”)

- U.S. v. Tot (3rd Cir. 1942) (“protection for the States” to maintain militia “against possible encroachments by the federal power”)

- U.S. v. Johnson (4th Cir. 1974) (“only confers a collective right”)

- U.S. v. Johnson (5th Cir. 1971) (applying Miller)

- Stevens v. U.S. (6th Cir. 1971) (“right ‘to keep and bear Arms’ applies only to the right of the State to maintain a militia”)

- Gillespie v. Indianapolis (7th Cir. 1999) (“appears on its face to secure a collective right (in much the same way … Tenth Amendment guards state sovereignty)”)

- U.S. v. Nelsen (8th Cir. 1988) (“protect[s] state militias”)

- Hickman v. Block (9th Cir. 1996) (“meant solely to protect the right of the states to keep and maintain armed militia”)

- United States v. Oakes (10th Cir. 1977) (“assure the continuation of the state militia”); United States v. Wright (11th Cir. 1998) (“inserted into the Bill of Rights to protect the role of the states in maintaining and arming the militia”)

- No D.C. Cir. decision, but see Sandidge v. United States, 520 A.2d 1057, 1058 (D.C. 1987) (“protects a state’s right to raise and regulate a militia”)

This understanding was so settled that the authoritative Black’s Law Dictionary (8th ed. 2004), four years before Heller, defined militia as “A body of citizens armed and disciplined, especially by a state, for military service apart from the regular armed forces. The Constitution recognizes a state’s right to form a ‘well-regulated militia,’” citing the amendment.

Look here, not over there

Surprisingly, the Heller Court, and both sides of the gun debate, ignored the centuries-old militia system, the chief focus of the unanimous Miller Court.

Likewise, the first constitution, whose war powers provisions were largely copied by the U.S. Constitution. The Articles of Confederation expressly provided that “every state shall always keep up a well-regulated and disciplined militia, sufficiently armed.” The U.S. Constitution appeared to shift these express powers from the States to Congress—which Antifederalists protested went too far and which the 2nd Amendment was meant to resolve.

In short, Heller and conventional wisdom, assuming away the state right actually debated and recognized throughout the 20th century, overlooked constitutional text, the militia system, and even the first constitution. Imagine what other parts of 2nd Amendment history they missed.

Implications for Heller, and America

What both sides of the gun debate and Heller did to the 2nd Amendment—advocating and declaring an individual right that was not debated and does not exist—was a historic legal blunder. What resulted is a dangerous decision, having devastating effects across our country, that keep worsening.

Heller is fatally flawed, based on profound misreadings of the amendment and founding, and vulnerable. Not only due to glaring mistakes in the text it did address, but because, having overlooked the prohibition “shall not be infringed” and never addressing the full text, it cannot legally stand. To learn more, visit Gun Crisis, About AEP, Problem Turns Epidemic, and Heller’s 2nd Amendment.

Proving the amendment’s true meaning, we can overturn Heller and return to legislatures the power to keep Americans safe. Will you join us?

We are a non-profit 501(c)(3) organization.

We are a non-profit 501(c)(3) organization.

Gifts to the American Enlightenment Project are tax-deductible.