In a tribute to Justice John Paul Stevens, who died July 16 at 99 years old, Time To Heed Justice Stevens’ Criticism Of Gun Decision (Law360 July 19, 2019), Robert Ludwig notes perhaps none “would have gratified him more than for the country to finally look to District of Columbia v. Heller to understand how it worsens gun violence, as he warned to the end. Better yet, to find a way to overturn it.”

In his memoir published in May, Justice Stevens called the 5-4 Heller decision, discovering for the first time in 200 years a blockbuster right to possess guns, “the worst self-inflicted wound in the Court’s history.” He revealed a memo circulated before Justice Antonin Scalia completed his majority opinion, hoping the “negative consequences” “all justices could foresee” would give “pause before announcing such a radical change in the law that would greatly tie the hands” of lawmakers seeking “solutions to the gun problem.”

Heller turned America’s “Gun Problem” into a “Gun Epidemic”

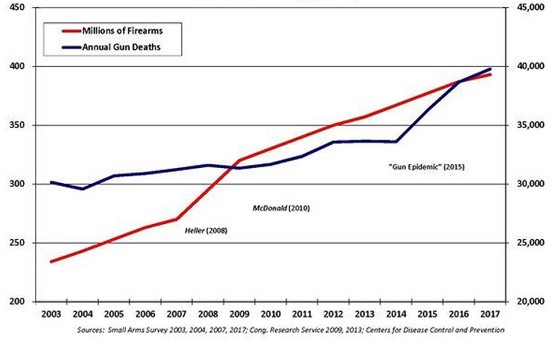

As Justice Stevens anticipated, America’s “gun problem” soon became a “Gun Epidemic,” declared in a page-one New York Times editorial in 2015. It keeps growing, year after year.

“The numbers tell the story,” Mr. Ludwig points out. “After Heller declared a constitutional right to guns in 2008, extended to the states by McDonald v. Chicago in 2010, guns and annual gun deaths surged in tandem, from 310 to 400 million and 31,500 to 40,000, as seen in this graph:”

to Heller and its negative consequences, the nation now has record gun violence, daily mass shootings, and weekly school shootings, triggering last year’s March for Our Lives.

“Not only was this ‘foreseeable’ to the Heller justices,” Mr. Ludwig writes, courts have long known that “unchecked gun proliferation and use tend to lead to impulsive, confrontational behavior, with deadly results. In 1832, a legal treatise cited in Heller condemned the practice of carrying loaded pistols, noting they ‘frequently turned a quarrel into a bloody affray, which otherwise would have terminated in angry words.’”

A Way to Overturn Heller Is “Desperately Needed”

Repeating his past warnings about Heller, Justice Stevens’ memoir was more emphatic: An amendment “to overrule Heller is desperately needed to prevent [more] tragedies.”

But “treating Heller and the Second Amendment as the rock and a hard place,” Justice Stevens “viewed revision or repeal of the amendment as the easier course.” Yet “it doesn’t need changing,” Mr. Ludwig explains, “serves too important a purpose in our complicated federal system, and means something other than what [all justices] believed.”

“There is a way to overrule Heller, hiding in plain sight,” as Mr. Ludwig pointed out in 2nd Amendment Still Undecided, Hiding in Plain View (Law360 Jan. 11, 2016), published the month after the ‘gun epidemic’ was declared and a month before Justice Scalia’s death. Quite simply, “Heller never decided the full Second Amendment. And having overlooked pivotal text, it cannot legally stand.”

A Historic Legal Blunder

As similarly explained in another article, The Historic Legal Blunder That Enabled Our Gun Epidemic ((Law360 Apr. 25, 2018), Heller surprisingly did not address the full amendment before the court. “Overlooking the prohibition and verb on which the amendment rests, Justice Scalia transposed ‘shall not be infringed’ to ‘abridged,’ though not synonyms as is obvious from any thesaurus, but constitutional terms of art,” as should be. “Infringe,” Mr. Ludwig relates, was invoked in the Second Amendment and throughout founding history “to protect public rights, of states over their militia.” “‘Abridge’ has been used the last 230 years — for the ‘great rights’ in the First Amendment, where the first Congress rejected the substitution of ‘infringe,’ and in all such amendments since — to protect private rights.”

Overlooking text is “‘the strongest reason for not following a decision,’” the California Supreme Court said in correcting a 140-year oversight, a “remarkable failure of the adversary system.” Because “relevant language and history” was not addressed, it held its prior case “cannot stand.” Having not addressed the Second Amendment’s full text and history, nor can Heller.

A Better, Validated Approach

As Mr. Ludwig further observes, “Heller’s oversights of legal distinctions — infringe and abridge, public and private rights — are part of a larger failure to understand founding and Enlightenment principles that underlie American constitutionalism.”

He cites as validation a near-unanimous patent infringement decision last year that distinguished public and private rights. Justice Clarence Thomas wrote: “This Court has long recognized the grant of a patent is a ‘matter involving public rights,’” not “private rights,” correcting the common fallacy that “most everyone considered a patent a personal right,” as Justice Neil Gorsuch assumed in dissent.

That 7-2 opinion did not consider the obvious: “what ‘infringement’ means in relation to patents (i.e., why the doctrine is not ‘patent abridgement’).” Yet, Mr. Ludwig notes, “it shows how quickly misconceptions can be corrected, even by justices in the Heller majority like Thomas.” And “correcting Heller will be even more decisive, finally putting to rest any notion of a private right.”

Blind Spots Are Putting American Lives at Risk

For courts and lawyers, and “constitutional scholars who call the amendment’s text baffling and beyond comprehension, not to know infringe and abridge are constitutional terms of art — no more interchangeable than ‘patent infringement’ and “patent abridgement” — is a serious problem,” Mr. Ludwig writes.

Similarly, it is “troubling enough” that Heller’s majority and dissents all “found variants of an individual right the other called ‘absurd,’” the decade after former Chief Justice Warren Burger denounced that notion as “the greatest piece of fraud.” But “for the majority to transpose the people’s right to bear arms to a facetious right to ‘to carry [handguns] in the home,’ Heller’s precise holding, forgets what the Court ‘must never forget, that it is a constitution we are expounding.’” Likewise, “for the dissents to find a right that was also a duty (to bear arms in a militia, subject to state fines and imprisonment if not exercised) — unlike any other individual right — makes no sense,” a contradiction that “should have been a telltale sign the interpretation is wrong.”

As Mr. Ludwig further raises, “for Heller’s majority and dissents, and thousands of lawyers and courts applying its related right — to use weapons ‘typically possessed by law-abiding citizens for lawful purposes’ — not to check its support, is another dereliction.” Closely read, “That ‘common use’ fiction rests on a single case, involving billy clubs, which miscites, and misreads, a picture-book encyclopedia on swords and bayonets.” Yet “that flimsy test has been enforced across the country to undo long-standing gun control.”

“These are but some of the many blind-spots and systemic oversights of conventional wisdom today,” he observes. “Others include the real meaning and sources of the Second Amendment: who determined its ‘baffling’ (actually clear) wording, when and why.”

And it is “with these blind spots, or worse, that national gun policy is now determined.” Meanwhile, Heller “is poised for extension to public carry, with government litigants still not challenging its flimsy test” in the lower courts or even a pending Supreme Court case, New York State Rifle & Pistol Ass’n v. City of New York, its first in a decade. In response, New York City announced it has changed its regulation, fearing another major loss like D.C. suffered in Heller and Chicago in McDonald, and urged that the case be deemed moot.

“Without a better approach,” he cautions, “that raises and allows the Court to correct historic error, such cases greatly increase the odds it will “soon expand Heller from the home to the streets, creating a new blockbuster right and level of gun violence.”

Enough is Enough: Decide the Actual Amendment

Concluding Mr. Ludwig writes: “Chief Justice John Roberts has from time to time called out ‘when this Court needs to say enough is enough.’”

It’s “past time for the courts, bar and academy to address the full Second Amendment. To stop assuming away text and longtime meaning. To stop turning a ‘gun problem’ into a ‘gun epidemic,’ and one blockbuster right into another, once sensibly called a ‘fraud.’

“Enough is enough. And pay Justice Stevens an ultimate tribute: Overrule Heller.”

This blog is excerpted from Robert Ludwig’s article, © 2019 All rights reserved. For further information, contact Mr. Ludwig at rludwig@ludwigrobinson.com or 202-289-7603.

Robert W. Ludwig is an attorney at Ludwig & Robinson PLLC. He is counsel for the American Enlightenment Project, a 501(c)(3) nonprofit formed to end gun violence through education of the courts and public, and legal challenges to the Supreme Court decision in D.C. v. Heller.